BACK TO HOME PAGE

ABOUT A DOSSAN OF HEATHER

THE COMPANION CD

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FROM THE INTRODUCTION

SAMPLE TUNES

REVIEWS

Extracts from the Introduction to

A Dossan of Heather

by Stephen Jones

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about this collection—apart from the beauty of the

music—is that it is, in essence, a time capsule: it is composed mostly of tunes that

were played in a remote townland of southwest Donegal between 1925 and 1937, when Packie

first left home; many of them have rarely been heard since.

...

Packie is one of the last survivors of the last generation of traditional musicians to learn his music in a purely oral tradition. He was in his teens by the time neighbours returned from America with wind-up gramophones and records, and he was a grown man before there was a radio in his parents' house. He has never learned to read music, but has relied on a razor-sharp musical memory, honed to the point where he could memorize a lengthy ballad after two or three hearings, and even tunes that he heard played only once. His powers of recall are the reason we have been able to assemble this body of music.

Packie has remained strongly

attached to the music of his youth. He has often remarked that while he

was growing up, the tunes and songs "were in the air" around him; it was

inevitable that they should strike deep roots in such a sensitive musical

nature as Packie's. Just as he has never lost his accent, he has never

broken with the musical tradition of his home townland. Perhaps it is his

way of keeping alive his fond memories of the stimulating folk culture

that flourished so strongly when he was a boy, and which all had but vanished

within a few years of his leaving home.

...

Many of the tunes presented here Packie learned from members of his family or from

neighbours and visitors. A number were simply tunes being played for dancing in the local area,

and beyond that he knows nothing of their origins. Others were tunes of

songs, or were made from song tunes (Packie himself being the chief artisan

of these transformations). Many tunes Packie knows to be of Scottish origin;

often, these were brought back to Donegal from Scotland by migratory workers

(known as "tatty hokers"). At least fourteen of the tunes are Packie's

own compositions, on top of the half-dozen that he made out of existing

song tunes (and even, in one case, a hymn!).

...

A story for every tune

In most collections of

traditional music, all that is presented of a tune is the bare skeleton

of notes on the stave and perhaps a name. Even names are often lost in

the oral-transmission process, particularly in the pub or festival session,

where so many tunes are learned either on the spot or later, through tape

recordings. All this makes it easy to forget that every tune originated

with a particular player in a particular community, and had its own significance

and associations, its own story.

‘Some of the older folks had a little story attached to every tune they played. If it was an air, they'd tell you the bones of the story. If it was a jig, if there wasn't really a story behind it, they could tell you who used to dance to it. "Mary so-and-so wouldn't dance to any other tune than this one," because it was her favourite tune. They all had little stories attached to them, and the thing about it is, a hell of a lot of the stories were true.'

We have endeavoured to remain faithful to this tradition. Packie is now, of course, one of the "older folks" and, with his keen memory and gift for storytelling, has indeed a story for almost every tune. Where he does not, we have given whatever relevant information he could provide.

The cast of musical characters

The names of the neighbours and family members from whom Packie learned tunes

keep cropping up in the stories. A brief introduction to the most significant

of these musical influences seems appropriate here.

The names of the neighbours and family members from whom Packie learned tunes

keep cropping up in the stories. A brief introduction to the most significant

of these musical influences seems appropriate here.

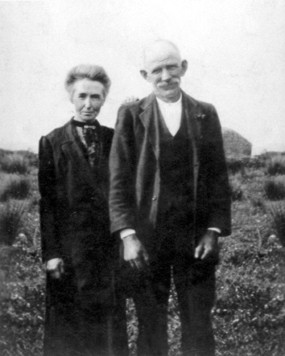

Although he did not play an instrument, Packie's father, Connell Byrne, was a keen lilter and storyteller. Packie's mother Maria (née Gallagher) also sang and lilted continually. Packie's grand-uncle "Big Pat" Byrne, a formidable fiddler and a formidable man, is one of the most important sources of tunes. Pat's sister Ann Byrne lived with her brother and has a tune named after her (Lilting Ann, no. 54).

Both of Packie's sisters, Ann and Memie, married men called Patrick Keeney. Ann's husband was a fine fiddle player. Two women named Bridget Sweeney were important figures in Packie's musical experience. The first, "Big Bridget" Sweeney (née Gallagher) was Packie's mother's aunt. The second was Biddy Sweeney of Corkermore. Both these women were noted singers and lilters.

Paddy Boyle, also known as Paddy Bhillí na rópaí, was a well-known fiddle player from Calhame, a townland near Killybegs. He was frequently invited to play at "big nights" (house dances) all over southwest Donegal.

Other influences were John Haughey, a fiddler from the townland of Gleann Baile Dubh; John Byrne (no relation), a fiddler from Ballywogs; Pat Kennedy, a melodeon player from Dunkineely; fiddler John Gallagher of Ardara and his father Paddy; and the Campbells from Silverhill, Glenties.

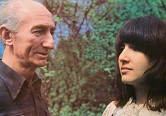

Another musician whose name occurs a number of times is Bonnie Shaljean. Packie

came into contact with her, not in the Donegal of the 1920s, but on the

London folk scene of the 1970s. Bonnie was a young American harpist and

singer with whom Packie formed a duo to perform in clubs and at festivals.

They played together for about ten years from the mid-1970s on and made

two LP records for Dingle's Records. One of the tunes in the collection

(no. 66) has been named after Bonnie. She now lives in Cork City, where

she plays and teaches Irish music on harp and keyboards.

Another musician whose name occurs a number of times is Bonnie Shaljean. Packie

came into contact with her, not in the Donegal of the 1920s, but on the

London folk scene of the 1970s. Bonnie was a young American harpist and

singer with whom Packie formed a duo to perform in clubs and at festivals.

They played together for about ten years from the mid-1970s on and made

two LP records for Dingle's Records. One of the tunes in the collection

(no. 66) has been named after Bonnie. She now lives in Cork City, where

she plays and teaches Irish music on harp and keyboards.

...

Characteristic

features of the tunes

Players who explore this

collection will soon come to appreciate the unique character of Packie's

tunes. They are simple and yet very alluring. Many have a distinctly Donegal

flavour, and nearly all have an ancient ring about them.

An immediately striking feature is the limited range of the melodies. Exactly two thirds of the tunes go no higher than f '. Of the remaining third, two tunes reach d" and six b' (the most common top note in Irish dance music). About 20 per cent of the tunes have a range of only one octave and another 15 per cent one octave and one note (d - e').

This restricted range

is almost certainly due to the fact that these tunes were frequently lilted,

and Packie's comments reveal that, despite the large number of fiddlers

in the area, the music for impromptu dancing sessions was very often provided

by a lilter. As noted above, many of the tunes were originally songs, but

the fact that the turn, or second part of the tune, keeps within the first

octave plus one or two notes reinforces the idea that these pieces were

lilted after their conversion into dance tunes. Packie's own compositions

keep within the same boundaries, for the same reasons, as his comment about

the reel Blow the bellows (no. 61), makes clear: "That's another one-octave

one. Makes them easier to sing!"

...

Packie's whistle style

The whistle is Packie's

main instrument, and his playing of it is unique. A discussion of his style,

apart from being interesting for its own sake, may help to shed light on

the transcriptions and suggest ways of approaching these tunes to players

less familiar with Donegal music.

In general, Packie is reluctant to enter into discussions of his whistle style. This is certainly partly due to modesty, but it may also owe something to the fact that in the Donegal of his youth the whistle was not taken seriously as an instrument for dancing to.

"Whistles were toys, they were for children. The day I was born there were whistles about the house, because my mother used to play the whistle a little. There was the old tapered one with the bit of timber in the mouthpiece, and 'twould lie up maybe for a year or so, and 'twouldn't be dried before it would be left lying up, and it would be red with rust, and the taste would be something shocking off it!

The first whistle I ever remember being my own, a fellow called Francie McGinley bought it for me. Now there was a christening somewhere, and Francie was a godfather to some youngster. At that time you had to take the youngsters all the way into Killybegs to get them christened, and there was a house in Killybegs, a shop called Quigley's, and it was the only place in this end of the county that you could get whistles. So he bought me a whistle and it cost one penny, and they were known as penny whistles at that time, which was another reason why they weren't regarded as very valuable.

My uncle Patrick Gallagher, my mother's brother, was a good whistler. I think he used to play for dancing, but there was always so many fiddle players around that nobody bothered with flutes or whistles or anything for dancing. All dancing was done to fiddle music. Fiddle was number one around here, and in fact it still is.

...

I don't know if I copied my uncle Patrick's style of playing the whistle. Maybe I did, unintentionally. I'm not sure about that."

Wherever the inspiration for his style came from, Packie's phrasing is very musical, and has— as we might expect from such an accomplished singer—a distinctive singing quality. Unlike many traditional flute and whistle players, who use tonguing sparingly or not at all, Packie admirably demonstrates the expressive possibilities of this technique. In fact, he makes more generous use of tonguing than perhaps any other whistle player in Ireland. There is a parallel to be made between Packie's employment of tonguing and the considerable use of single-stroke bowing by Donegal fiddlers.

Tongued triplets are a very noticeable characteristic of Packie's playing, occurring on the same note, or with the first note doubled and an adjacent note as the third component, and less frequently on three consecutive notes upward or downward. The parallel with fiddling is obvious here. To produce the tongued triplets, which are beautifully clear and even, Packie uses a technique derived from lilting: his tongue makes a "diddle-dee" movement rather than the "ta-ka-ta" recommended in classical flute or recorder technique.

"I do it with the tongue against the top of my mouth, but I cannot do it so well since I got the false teeth. When I had my own teeth I had much more room for the tongue to hop about! Yi-till-diddly, i-till-diddly... You could keep that diddly-diddly thing going all the time."

Packie will occasionally use tongued staccato at the end of a phrase or in particular sections of a dance tune to add expression or to suit a movement in the dance (Piddlin' Peggy slip jig, no. 29, The sapper dance, no. 12). The only tunes where Packie uses very little tonguing are marches. Perhaps this is in unconscious imitation of the highland pipes, or in order to create a flow that is more suitable for marching than for dancing to.

In Packie's view, many of the older generation of whistle players used tonguing quite frequently. In his own case, as he says above, he began to incorporate more tonguing into his playing when he began to lose agility in his fingers. Arthritis has for decades severely restricted movement of the second and third fingers of his right hand (and has ultimately caused him to stop playing altogether). As a result, Packie uses finger ornamentation sparingly in most tunes. "Cuts" (single grace notes) are played on E, F , G, A and B (never on C or D). In highlands, cuts and triplets are used interchangeably. Packie uses trills extensively in slow airs, but occasionally (and unusually) on longer notes in dance tunes.

The roll, that characteristically Irish and now ubiquitous ornament, is a device that Packie does not care for. He feels that, as used by many players, rolls tend to obscure rather than highlight the melody:

"To be quite honest, I'm not too keen on this rolling business, because I reckon it takes the flavour out of the tune, especially for the listener. It sounds good, especially on a whistle or a flute, but [without it] a listener can pick up the tune much easier. Now that's only my opinion, but I know what I like to listen to. I think really it has to do with the way the notes form in the tune."...

Packie has often quoted a favourite saying of his father's, expressing admiration of a gifted musician: "He could take music out of a fresh loaf!" I am sure that Packie's father must frequently have aimed this phrase at—if he did not coin it for—his second son. I am equally confident that readers, after "listening" to the stories and trying out the tunes preserved in these pages, will not only acknowledge the remarkable talent but also enjoy the warm personality and irrepressible humour of our friend Packie Manus.