HOME

NEWS

ABOUT PACKIE

A DOSSAN OF HEATHER

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

TALL TALES

DISCOGRAPHY

LINKS

QUESTIONS? CONTACT US!

SISTER SITES:

BRO. STEVE'S WHISTLE PAGES

SIAMSA SCHOOL OF IRISH MUSIC

Recollections of a Donegal Man

by Packie Manus Byrne, ed. Stephen Jones

Published 1989, reprinted 1992

240 pp.

Illustrated by Pierre Renaud

ISBN 0 9514764 0 8 (original print edition)

ISBN 978-0-9950053-0-3 (epub edition)

Now available in an eBook edition

Out of print for many years, Packie's Recollections is now available, in eBook format, to mark the centenary of his birth (18 February 2017). The eBook contains the complete text and all illustrations of the original print edition, with a new foreword for 2017.

Currently available from the Kobo bookstore, or from smashwords. Other outlets will follow soon.

Summary

Reviews

Contents

and extracts

Summary

Packie's autobiography was published in 1989. It is a treat for anyone who likes Ireland, traditional folk music, social history, or “who wants a good read and is looking for something a bit different”. Directly transcribed from taped conversations, the book sparkles with Packie's natural good humour and love of life.

The first half of the book is devoted to Packie's childhood and early manhood, with a wealth of fascinating detail about life in a remote corner of rural Ireland during the 1920s. There are chapters dealing with traditional music and song; fiddles and fiddle players; weddings, wakes and other celebrations; arts and crafts; housebuilding, and so on.

Packie

then goes on to chronicle his adventurous wanderings throughout Britain

and Ireland, giving a rare insight into the life of an ordinary working

man. There is plenty of good reading here too, with stories of smuggling

btween Northern Ireland and the Republic; descriptions of the old-style

country fairs and the characters that frequented them; and reminiscences

of such giants of Irish music as Séamus Ennis and Felix Doran.

Packie

then goes on to chronicle his adventurous wanderings throughout Britain

and Ireland, giving a rare insight into the life of an ordinary working

man. There is plenty of good reading here too, with stories of smuggling

btween Northern Ireland and the Republic; descriptions of the old-style

country fairs and the characters that frequented them; and reminiscences

of such giants of Irish music as Séamus Ennis and Felix Doran.

Packie's natural warmth shines clearly through the pages of Recollections of a Donegal Man, lending the book a charm that has won the hearts of readers and reviewers on both sides of the Atlantic.

On-line reviews

Here are links to an on-line reviews by the following writers:

Larry Sanger, creator of the Donegal fiddle homepage.

[Raymond Greenoaken, co-editor of beGlad magazine, wrote a nice review in Stirrings magazine. We're waiting for the new URL.]

What the critics say

“A fascinating personal, social and musical odyssey... Packie evokes [the vanished world of his childhood] with such skill that you can almost smell the turf fire, hear the scrape of the fiddle and the stamp of the feet on the earthen floor”

“Packed with folklore detail, couthy philosophy, humour, joy and sadness... It is a long time since I so thoroughly enjoyed a book of this kind”

“One of the delightful aspects of this book is that is written in the vernacular of South Donegal and is presented in the colourful way Byrne would tell a story. The result makes for unusual and excellent reading”

“... images ... as tactile, earthy, and gripping as those of Séamus Heaney's poetry"

“A marvellous story . . . Packie Manus Byrne [is] an international treasure”

“More than a readable book, [this] is also an important contribution to social history which will sit comfortably in any library”

Contents

Below is

the table of contents from Recollections of a Donegal Man.

Click on

a link to read extracts from the text

|

Copyright

notice

|

Introduction

1

Our Little Area Back Home

2 Farm

and Farm Life

3 Loaves

and Fishes

4 Church

and Community

5 School

and Schooling

6 Family

7

Weddings, Wakes and All This Caper

8 We Made

a Lifetime of It: Music, Dancing and Singing

9 A Country-house

Hooley

10

Such Likeable Music: Fiddles and Fiddle Players

11 The

Art of Survival

12 The

Old Thatched Cottages

13 Leaving

School and Leaving Home

14 First

Time Over to England

15 The

Makings of an Actor

16 Droving

Days and the Country Fairs

17 Wartime

18 Boosting!

19 King's

Lynn Years: Factory, Farm and Circus Hand

20 Early

1950s: Showman and Steeplejack

21 Singing

to Cure Sickness

22 Selling

Up the Old Farm

23 Early

Days on the Folk Scene 000

24 Manchester

Years: Some Memorable Characters

25 A New

Leaf in London

26 Black

Jack, and a Haunted House 000

27 Some

Reflections from Back Home 000

Afterword

by the Editor: A Visit to Corkermore 000

Appendix:

Discography

From the Introduction

Anyone who has ever met Packie Manus Byrne will relish the prospect of this book — as will anyone who has had the pleasure of seeing him perform during his long career, or who is aware of the respect and affection he inspires among lovers of traditional music. But those who have never heard his name before can also rest assured that a rare treat is in store for them.

For Packie Manus is a man of uncommon charm and talent, and the story he tells in these pages is a rich one, full of incident and historical detail, humour and wisdom. It spans the full breadth of the enormous changes that have occurred in the twentieth century, and gives us much to enjoy and ponder on along the way: there are poignant glimpses of a vanished way of life in the isolated crofting community in Donegal where Packie was born; vivid pictures of the bustle and excitement of the old-style country fairs in Ireland; the fun and risks of smuggling cattle and provisions across the border into the North; and many other hilarious incidents in the life of a wanderer who was always on the lookout for adventure. To counterbalance the humour there are hard times and personal losses, and a good deal of food for reflection on how much the modern world has lost in the way of tradition, colour and common sense. Nevertheless, the whole tale remains a celebration of a life enjoyed to the full.

Best of all, this tale is told by a born storyteller whose pleasure in sharing his story is irresistible. The vividness of Packie's words will make it easy for readers to imagine they are hearing the story from his mouth, as I myself heard it during the making of this book, with Packie comfortably seated in an armchair in his North London room, as often as not with a mug of strong tea in his hand, and always with a sparkle in his eye.

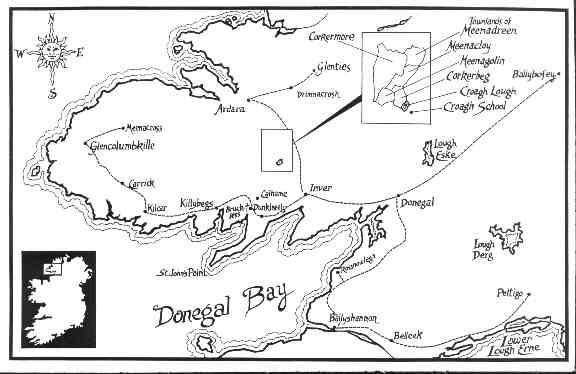

The story begins in 1917, in Donegal, a county in the extreme northwest of Ireland that is celebrated for its vigorous folk culture and the spectacular rugged beauty of its mountains and coastline. In the parish of Killybegs, ten miles or so inland from that picturesque fishing port, lies the townland of Corkermore; in those days it was a remote place not accessible by road and composed of eleven small farms or crofts scattered over the sides of a wind-scoured glen. Here, on 18 February of that year, Packie Manus was born, the youngest of the four children of Connell and Maria Byrne.

As in the isolated country areas all over Ireland, the twentieth century was slow to make its impact, and many aspects of life at the time can have changed little for generations. Singing, dancing and storytelling were still the principal forms of entertainment. Packie's parents and many neighbours were noted singers and storytellers, and a fiddle hung on the wall of almost every house. In their leisure hours people went "rambling" — visiting — in search of entertainment and amusement. Little excuse was needed for the fiddle to be taken down and a vigorous session of dancing to begin. Surprising as it may seem, in those days it was quite usual to find people walking through the area at literally all hours of the night, on their way home from a dance, music session or gathering in a neighbour's house or further afield.

The richness of social life was a vital compensation for the rigours of hill-farming existence. The winters were harsh, and the Atlantic gales frequent and fierce. Ill-health, especially tuberculosis, was always close at hand. The land was poor — much poorer than that in some surrounding areas; much of it consisted of treacherous mires, or swamps, and the green fields suitable for hay and cropping had been won by generations of draining, manuring and digging with spades. There was however an abundance of first-class peat bog to provide fuel, and turf (peat) could be sold in the towns or bartered for other commodities.

During the summer months men (and often women and children as well) worked long hours in the fields in order to provide enough food for their families, many of which were large. In the winter, when there was little to be done on the land, many of the men left in search of paid work. Scotland was a popular destination, and Packie's father, before he had children, went there many times. The winter also allowed people to devote more of their time to traditional crafts and to music, in both of which fields they were highly skilled.

Naturally enough, in those times people were self-sufficient to a degree that has no parallel today. Indeed, the community as a whole was self-reliant, and neighbours would help one another to weather bad times. There was also great neighbourliness and mutual respect between Catholics and Protestants in the area, as Packie's stories make clear. (This neighbourliness did not, however, restrain them from playing fierce practical jokes on each other, some choice examples of which are recounted by Packie.) All this was part of an approach to life that Packie often refers to as "the art of survival" — an apt term for what is an important part of the way he himself looks at the world: it encompasses the ability to get by on very little and enjoy life at the same time, an inbred talent for improvisation and self-sufficiency, and the knack of living harmoniously with other people.

This, then, was the community into which Packie Manus was born in 1917: a culture with a traditional heritage and identity which was still flourishing even though it was, as we shall see, on the verge of destruction...

...

Chapter 1 : Our Little Area Back Home

If ever you are up in the southwest part of County Donegal, and you're moving in a straight line between the port of Killybegs and the town of Glenties, or between Ardara and Dunkineely, you've a fair chance of trespassing in the area where I was born and brought up — a little townland called Corkermore. Now you won't find it on a map today: the nearest place you might find would be Croagh, which was four or five miles away from our place, where I went to school. But Corkermore was like the hub of a wheel, with Ardara, Killybegs, Dunkineely and Glenties all about the same distance away around the rim of the wheel.

I

was born into a time when life, for my parents and the generation above

me, was a bit tough. The people back home were all small farmers, crofters.

The land was very poor, and they had to work very hard on it to get any

kind of a living out of it. There was hardly any money, and they had a

method of living, not from each other or off each other, but with each

other. Now four or five cows was as much as any farm could support, because

the grass wasn't good enough to feed any more, and when some of them would

be drawing near calving, say March, April, naturally they wouldn't be giving

any milk. There was no danger that the youngsters would go without milk

or butter, because some neighbour had cows that were giving milk, and they

would hand it out. The same applied if you had a job to do, like hauling

something over the mountain and it was too heavy to carry: if you didn't

have a horse, well some neighbour would give you a horse for the job.

I

was born into a time when life, for my parents and the generation above

me, was a bit tough. The people back home were all small farmers, crofters.

The land was very poor, and they had to work very hard on it to get any

kind of a living out of it. There was hardly any money, and they had a

method of living, not from each other or off each other, but with each

other. Now four or five cows was as much as any farm could support, because

the grass wasn't good enough to feed any more, and when some of them would

be drawing near calving, say March, April, naturally they wouldn't be giving

any milk. There was no danger that the youngsters would go without milk

or butter, because some neighbour had cows that were giving milk, and they

would hand it out. The same applied if you had a job to do, like hauling

something over the mountain and it was too heavy to carry: if you didn't

have a horse, well some neighbour would give you a horse for the job.

Very often, when it would come to clipping sheep, a neighbour would come and give a hand. When it came to washing wool or washing yarn, some of the neighbour women would come along and join with my mother. And that applied to everything — building houses, handling cattle, building ditches. Everything was, "do unto others as you wish others do unto you'.

I don't

know if you've ever heard of "bastings'. That was the first milk from a

cow after she would calve. 'Twas yellow milk. It was distributed around

as a sort of gesture, to show the neighbours that, well, you won't go short,

because this cow has calved, and there's milk. The calf got some of the

first milk, but the neighbours got the remainder. This milk was different,

because when you boiled it, it got solid, it got a bit like yogurt, only

it tasted beautiful. You could eat it then with a spoon. You could eat

it with a knife and fork, in fact: cut it down and eat it in slices. That

was a favourite custom of the people back home, to distribute some of the

first milk from the cow.

...

Corkermore was a big townland: there were only eleven houses, but they were all scattered, dotted all around the hillside. The houses were all almost identical: one-storey cottages with thatched roofs made of oat straw. From our house you could see up to thirty dwellings, but only three were of Corkermore. There were three more houses about half a mile further down the river, and there were four more straight over the hill behind our place facing the west. The other dwellings you could see were over the river in the townlands of Meenacloy and Meenadreen, and if you moved around a bit from our door you would see little bits of the cluster of houses in the townland of Meenagolin, which was up on top of a hill. The name means in Irish "the plain of the upper arm', from the shape of the land and the formation of the hills.

Neighbours often dropped in. You never thought to enquire what they wanted, because they didn't want anything, just came in for a chat, and to spread their own news and gather other people's. If someone dropped in from another townland, say from beyond the river — it might be only a mile away, the first word my father would say would be,

"Well, what's the news from your area?"

My father couldn't even wait until somebody would start talking casually about something that had happened, he had to know right away what was the news. Of course, that's the only way news could be spread, by people walking about. It was simple kind of news — someone went over to Scotland, or someone came home from America, or someone sold some sheep, or someone's mare had a foal; or how far people in the area were advanced with crop planting, or cutting turf. World events and politics weren't mentioned so much (owing to the fact that very few people understood either!), and so work was the main topic of conversation. If it so happened that the night before there had been a gathering or a "big night" (where people gathered to dance, sing and play music) that would be talked about, and who was at this gathering, because everybody knew everybody.

So they

would sit around the fire and chat and smoke. My father would caulk his

pipe and light it, and when he had it going good he offered it to the visitor.

Even they weren't smokers, most people took two or three pulls out of it

and handed it back to my father or on to the next person. The women would

smoke pipes too, the older ones. They would be clay pipes, and they were

usually left over after wakes. Someone would die, and this would be the

entertainment for the people who would gather round to sympathise with

the bereaved: they were all given clay pipes. They were snow white, and

they burned the mouth off you when you tried first time. Then as they went

on in years they got more mellow and became blacker, because the soot out

of the chimneys and the smoke coming through the stem blackened the pipes

till you would think they were wooden pipes, but they weren't. Some people

used to break the stem so that they would be hotter. Some of them would

have a stem only about two inches long, and they would be holding the bowl

almost against their cheek and puffing away like an engine!

...

Chapter 7: Weddings, Wakes, and All this Caper

But I think the best time of the year was what we called the putting in of the hay, that was drawing in the hay. Now they didn't have haysheds or no buildings to store the hay in: the hay was built in big long stacks and then thatched over like the roof of a house, and roped down. We used to have some fun building haystacks.

I remember one haystack we were building, oh indeed my father was there and he was one of the ringleaders; this man that owned this hay, he had a beautiful ladder, brand-new, 'twas about 25 or 30 feet long. The ladders would be all gathered from the neighbourhood so as that four or five men could be thatching at the same time, because the stack was drawn in, built, thatched, roped, finished, all in one day. So when it came to the evening time to do the thatching, this man's ladder was lost; no-one knew where it was. Well a few did but they weren't going to tell, including me and my father. The man was really worried, he could not figure out where his ladder was, and he told everywhere that his ladder was stolen. He told the guards that his ladder was stolen, and they were out looking for the ladder, out on bicycles and questioning likely subjects and all.

But when it came to using the hay, around October when this man started taking the hay out of this big stack he came on his ladder. The ladder was built in the stack of hay! And the hay was beaten down, tramped down in between the rungs of the ladder, so he couldn't get it out. He used and used away at the hay and naturally the stack was getting shorter, and there was the ladder sticking out, and it was there the whole winter, till the month of March, till he had the last dash off the haystack and he could lift out the ladder, and by that time it got so much abused from rain and snow and all, it was almost rotten!

Until the day he died he was never told who was responsible for that. Three or four of us done that while the rest were in the house and having a meal. The rooms were small and the tables were small, so very often they would eat in two lots. So we said, oh, we'll stay, go on, you fellows were earlier than us. And he was so proud and careful of that ladder. He wouldn't leave it in the sun because it would warp, he wouldn't leave it out in the rain because the timber would get soggy, and in spite of that it was out the whole winter.

There was another case: this bloke, he was the first in our area to wear Wellington boots, which we just called rubber boots. Wellington boots weren't really the fashion in the old days — the men all wore hobnailed boots, and what they called searacháns (that was pieces of hay rope or little leather straps tied around the trousers below the knee to save the wear on the knees of the trousers, and to lift the bottoms out of the muck and the dew, and to keep you from tripping over the trousers while you were working or carrying something). So, this fellow got a pair of Wellington boots and everyone was admiring them and they were so useful: you could walk through wet meadowland, you could walk through swamps, oh they were the greatest thing. He was a very good haystack builder, this bloke, but he always built in the stockinged feet. Wading through soft hay all day with Wellington boots is a bit tiresome, so he took them off and put them away behind a clump of trees or little bushes that was growing near the haystack. I wasn't in on this deal, but I think my father was. When it came towards late afternoon and the stack was finished, your man came down; having the stack finished he was admiring his work. He went over to the clump but there were no Wellingtons. The Wellingtons were built in the haystack.

Now if they

were built anywhere near the working end of the haystack, he could have

them earlier in the year, but they were put right at what we called the

stern, which was the far end that would not be touched because that was

facing the storm — like there was a method in all this: in our area all

the storm comes from the west and the south-west, so if you're building

a haystack you put this stern end, very well built and raked and padded

down and very well thatched, towards the storm, so that the hay wouldn't

get damaged, and you worked out of what we called the sheltry end, the

mouth, and worked backwards. So he had to go the whole long winter without

Wellingtons, he was back to the

hobnailed

boots again, and oh he was in a right bad way about that. He didn't get

them till maybe the end of March.

Oh, there used to be some funny things done. And they weren't f done out of spite — the man who lost the ladder was very well liked in the area. But nobody took much notice because that kind of thing was expected. Then there would be a little dance, a little country-house hooley, at that farmer's house that night, and all the caper that was done during the day was forgiven. Especially after a few drinks, dances, songs, tunes and stories, all in the company of pretty young girls.

...

Chapter 10: Such Likeable Music: Fiddles and Fiddle Players

Fiddles were as plentiful as stones in our area. There were fiddles all over the place — in nearly every house. That was part of the furniture! You went into a house and the first thing that struck your eyes was a fiddle, and the fiddle was always hung in one particular place, above the fireplace, on what they used to call the "brace" of the house.

None of the fiddles had cases. The fiddle players, if they were going away to play somewhere, they wrapped a sack or an overcoat or a mac around the fiddle and put it under their arm and went away over the mountains, even in pouring rain; and the fiddles would all play, I don't know how. But nobody ever had a case for the fiddle, because they said that was the ruination of a fiddle, to put it in a case. If you left a fiddle in a case, it was never the same again. When they came home, that fiddle was hung on the brace.

Now the

smoke from the fire went up behind the big flag, and the fiddle was hung

on the outside of the flag, and it was always kiln dry. And a lot of them

fiddles were probably a light colour when they were new. But they were

all jet black; the turf smoke blackened them so much that in the dark you

wouldn't see them! And the dust of the fire would settle on them. I remember

Big Pat Byrne, my gran'uncle, when he would take down his fiddle, the first

thing he'd do was blow the dust off it. But they were always against the

cases.

...

Now my gran'uncle Big Pat was very well known. He used to go away for days at a time with the fiddles and the gun, away shooting birds and hares and rabbits and playing the fiddle. Wouldn't come back for a couple of days maybe; and his relations never worried about him because they knew that he was in somebody's house, he was all right. Too drunk to come home, or whatever was the excuse!

He had a long white beard. He was about six feet three and built like a tea chest, square as could be. I was only something like fourteen or fifteen when he died. And he died with maybe a thousand old tunes. Not one of his family would bother about collecting them, because by the time Pat died we were getting interested in modern music, learning the waltz and the foxtrot! Mind you, I can still remember quite a few of Big Pat's tunes today.

Now I don't want to say this too loud, because I could get into trouble over it. They'll talk about the Byrnes and the Dohertys and the lot, but I think Big Pat was about the best fiddle player. He could play rings around Paddy Boyle, anyway. Yes, Big Pat was very good. And do you know, he had only three fingers on his left hand. He was cleaning a gun when it accidentally went off and blew off one of his fingers; I forget which finger it was, but it was one of the two middle ones anyway. Yes, he had only three fingers on his left hand, but he could play as good as anyone.

Big Pat

had some strange sayings. He could be very scathing of other musicians

— mostly fiddle players: he didn't think any other instrument was worth

listening to. If someone wasn't playing well, and wasn't taking out all

the notes and the long draws of the bow and all this, he used to say,

"Och, there's

no venom in his music!"

If he saw

some other fiddle player scraping away furiously, he would call that "sawing

the fiddle in half with the bow". Or if

the fiddle

player's elbow was jumping up and down while he was playing, Pat would

reckon that he was "just scratching himself"! Because in Pat's idea, the

elbow should hardly move anyway, except back and forward; it should not

go up and down — I don't know if he's right or not, probably he was. There

was a method to everything he said. Even though it was mad there was a

method to it. Oh, they had their ways of saying things.

It's possible

that Big Pat and Paddy Boyle might be considered a bit rough and ready

beside some of the best today, but they played really nice music, and they

played only the best tunes: if they picked up a new tune and found that

it didn't seem to fit the fiddle music, they scrapped that one. John Doherty,

till the day he died, had the same habit. If it wasn't a tune that he thought

was reasonably suited to a fiddle, he didn't play it, he left it away.

Pat would do the same, Paddy Boyle would do the same, and very likely if

you mentioned a certain tune to one of them, he might say, I can't remember

that'un. He knew it right well, but it wasn't a good fiddle tune, so he

wouldn't play it. I think that habit is what kept the traditional music

going.

...